The Scan Matching Problem

When we run scan matching, we usually have two point clouds:

- a source scan $S_1 = {\mathbf{p}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{p}_n}$ (the new measurement), and

- a target scan $S_2 = {\mathbf{q}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{q}_m}$ (a previous scan or a global map).

Our goal is to find a rigid transform $(R, \mathbf{t})$ that best aligns the source to the target.

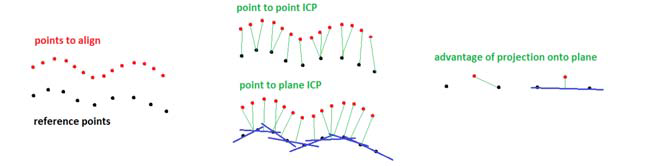

Point-Point ICP

If the two clouds are perfectly aligned, each transformed source point $R\mathbf{p}_i + \mathbf{t}$ would land exactly on its counterpart $\mathbf{q}_i$.

In practice there’s noise and partial overlap, so we instead minimize the sum of squared distances between matched points.

For a pair of matched points $(\mathbf{p}_i, \mathbf{q}_i)$, define the residual

\[\mathbf{e}_i = \mathbf{q}_i - R\mathbf{p}_i - \mathbf{t}.\]Stacking all correspondences gives us a cost

\[J(R, \mathbf{t}) = \sum_{i} \|\mathbf{e}_i\|^2 = \sum_{i} \|\mathbf{q}_i - R\mathbf{p}_i - \mathbf{t}\|^2.\]The Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm is a classic way to minimize this cost when we don’t know the correspondences in advance.

Classic Point-to-Point ICP Loop

The vanilla point-to-point ICP algorithm alternates between two subproblems:

- Find correspondences (given the current pose).

- Estimate pose (given the current correspondences).

You repeat this until convergence.

If we write the state vector as

\[\mathbf{x} = [\boldsymbol{\theta}, \mathbf{t}]\]where $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ is a minimal representation of the rotation (e.g., axis-angle or small roll–pitch–yaw),

The key trick is the linearization. Around the current estimate $(R, \mathbf{t})$, we approximate how the residuals change with a small pose increment $d\mathbf{x}$. For point-to-point ICP, the Jacobians for each correspondence are:

\[\mathbf{e}(R, \mathbf{t}) = \mathbf{q}_i - R\mathbf{p}_i - \mathbf{t} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \frac{\partial \mathbf{e}}{\partial \mathbf{t}} = -I_{3 \times 3}.\]For rotation, we apply a small perturbation $(\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}, \delta\mathbf{t})$ to the current pose:

\[R' = R \exp([\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}]^\wedge), \quad \mathbf{t}' = \mathbf{t} + \delta\mathbf{t},\]where $[\cdot]^\wedge$ is the hat operator, giving the skew-symmetric matrix:

\[[\mathbf{p}_i]^\wedge = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -p_{i,z} & p_{i,y} \\ p_{i,z} & 0 & -p_{i,x} \\ -p_{i,y} & p_{i,x} & 0 \end{bmatrix},\]and $[\mathbf{p}_i]^\wedge \delta\boldsymbol{\theta} = \mathbf{p}_i \times \delta\boldsymbol{\theta}$.

For small $\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}$, $\exp([\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}]^\wedge) \approx I + [\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}]^\wedge$.

Starting from the perturbed residual with small perturbation (δθ, δt):

\[R' = R \exp([\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}]^\wedge), \quad \mathbf{t}' = \mathbf{t} + \delta\mathbf{t}\]We get:

\[e' \approx \mathbf{q}_i - R(I + [\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}]^\wedge)\mathbf{p}_i - \mathbf{t} - \delta\mathbf{t}\] \[= \mathbf{q}_i - R\mathbf{p}_i - R[\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}]^\wedge \mathbf{p}_i - \mathbf{t} - \delta\mathbf{t}\]Factor out the original residual e₀ = qᵢ - Rpᵢ - t to get:

\[e' \approx e_0 - R[\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}]^\wedge \mathbf{p}_i - \delta\mathbf{t}\]Using the cross-product antisymmetry identity:

\[[\delta\boldsymbol{\theta}]^\wedge \mathbf{p}_i = \delta\boldsymbol{\theta} \times \mathbf{p}_i = -\mathbf{p}_i \times \delta\boldsymbol{\theta} = -[\mathbf{p}_i]^\wedge \delta\boldsymbol{\theta}\]We get:

\[e' \approx e_0 + R[\mathbf{p}_i]^\wedge \delta\boldsymbol{\theta} - \delta\mathbf{t}\]From this linearization, the Jacobians are:

\[\frac{\partial e}{\partial \delta\boldsymbol{\theta}} \approx R[\mathbf{p}_i]^\wedge, \quad \frac{\partial e}{\partial \delta\mathbf{t}} = -I\]From per-point Jacobians to the global least-squares system

For each correspondence $(\mathbf{p}_i, \mathbf{q}_i)$, we have a residual:

\[\mathbf{e}_i = \mathbf{q}_i - R\mathbf{p}_i - \mathbf{t} \in \mathbb{R}^3\]and its linearization with respect to the pose increment:

\[\delta\mathbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} \delta\boldsymbol{\theta} \\ \delta\mathbf{t} \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^6\]is:

\[\delta\mathbf{e}_i \approx J_i \, \delta\mathbf{x}, \quad J_i = \begin{bmatrix} R[\mathbf{p}_i]^\wedge & -I \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{3 \times 6}\]Stacking all correspondences:

Define the global residual vector and Jacobian matrix by stacking over all $N$ correspondences:

\[\mathbf{e} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{e}_1 \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{e}_N \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{3N}, \quad J = \begin{bmatrix} J_1 \\ \vdots \\ J_N \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{3N \times 6}\]The cost function:

\[F(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^N \|\mathbf{e}_i\|^2 = \frac{1}{2} \|\mathbf{e}\|^2\]Linearization:

Around the current estimate $\mathbf{x}$, we linearize:

\[\mathbf{e}(\mathbf{x} + \delta\mathbf{x}) \approx \mathbf{e}(\mathbf{x}) + J \, \delta\mathbf{x}\]Substituting into the cost:

\[F(\mathbf{x} + \delta\mathbf{x}) \approx \frac{1}{2}\|\mathbf{e} + J\delta\mathbf{x}\|^2\]Solving for the update:

Setting the derivative to zero:

\[\frac{\partial F}{\partial \delta\mathbf{x}} = J^\top (\mathbf{e} + J\delta\mathbf{x}) = 0 \quad \Rightarrow \quad J^\top J \, \delta\mathbf{x} = -J^\top \mathbf{e}\]This is the normal equation of the Gauss–Newton step. Define:

\[H = J^\top J = \sum_{i=1}^N J_i^\top J_i, \quad \mathbf{b} = -J^\top \mathbf{e} = -\sum_{i=1}^N J_i^\top \mathbf{e}_i\]We obtain the linear system:

\[H \, \delta\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{b}\]Solve this at each ICP iteration to update the pose:

\[\mathbf{x} \leftarrow \mathbf{x} \oplus \delta\mathbf{x}\]Algorithm Implementation

The pseudocode looks like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

def pt_pt_icp(pose_estimate, source_scan, target_scan):

"""Point-to-point ICP algorithm."""

# Build an acceleration structure for nearest neighbors

build_kd_tree(target_scan)

for iter in range(MAX_ITERS):

errors = []

jacobians = []

# 1. Correspondence step: associate each transformed source point

# with its nearest neighbor in the target scan

for pt in source_scan:

pt_map = pose_estimate * pt # transform into target/map frame

pt_map_match = kd_tree_nn(pt_map) # closest point in target_scan

e = pt_map_match - pt_map # residual

errors.append(e)

# Jacobian of e w.r.t [theta, t]

# Using e = q_i - R p_i - t with current pose estimate

J_rot = pose_estimate.rotation() @ hat(pt_map) # ∂e/∂R ≈ R [p]^∧

J_trans = -np.eye(3) # ∂e/∂t = -I

J = np.hstack([J_rot, J_trans])

jacobians.append(J)

# 2. Linearized least squares step (Gauss–Newton)

# Solve H dx = b for the pose increment dx

H = sum(J.T @ J for J in jacobians)

b = sum(-J.T @ e for J, e in zip(jacobians, errors))

dx = np.linalg.solve(H, b)

pose_estimate = pose_estimate.oplus(dx) # update R, t using the increment

# 3. Convergence check

if total_error_change_small():

break

return pose_estimate

- Iterative methods are relatively simpler, though. It works as long as the cost landscape is decreasing from the current estimate to the global minimum.

Point-Plane ICP

If we write out our state vector as [theta, translation], the pseudo code for point-plane ICP is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

pt_plane_icp(pose_estimate, source_scan, target_scan):

build_kd_tree(target_scan)

for n in ITERATION_NUM:

for pt in source_scan:

pt_map = pose_estimate * pt

N_pt_map_matches = kd_tree_nearest_neighbor_search(N, pt_map)

plane_coeffs = fit_plane(N_pt_map_matches)

errors[pt] = signed_distance_to_plane(plane_coeffs, pt_map)

jacobians[pt] = get_jacbian(plane_coeffs, pt_map)

total_residual = errors* errors

H = sum(jacobians.transpose() * jacobians)

b = sum(-jacobians * errors)

dx = H.inverse() * b

pose_estimate += dx;

if get_total_error() -> constant:

return

The Point-Plane ICP is different from Point-Point ICP in:

- We are trying to fit a plane instead of using point-point match

- In real life, we need a distance threshold for filtering out distance outliers.

Also note that:

- A plane is $n^T x + d = 0$. The plane coefficient we get are $n, d$

- The signed distance between a point and a plane is:

- The jacobian of error is:

Point-Line ICP

The point-line ICP is mostly similar to the point-plane ICP, except that we need to adjust the error and Jacobians.

A line is:

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & d \vec{r} + p_0 \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]We choose the error as the signed distance between a point and it is :

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & e = \vec{r} \times (R p_t + t - p_0) \\ & = \vec{r} ^ \land (R p_t + t - p_0) \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]The jacobian is:

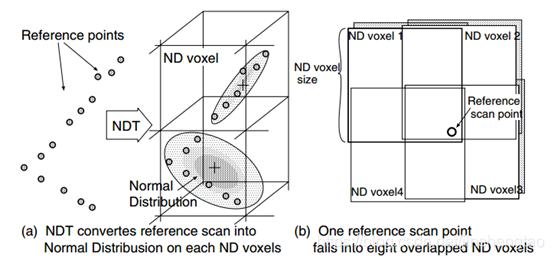

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & \frac{\partial e}{\partial R} = - \vec{r} ^\land R p_t^{\land} \\ & \frac{\partial e}{\partial t} = \vec{r} ^\land \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]NDT (Normal Distribution Transform)

- Voxelization. Partition the target point cloud into voxels. For each voxel, compute:

- Mean: $\mu$

- Covariance matrix: $\Sigma$

- Point-to-Distribution Association (for each source point). For each point $p_t$ in the source scan:

- Transform to map frame using current pose estimate: $p_t = Rp_t + t$

- Voxle Lookup. Find the voxel containing $pt$ in the target map. Retrieve $\mu$ and $\Sigma$ of that voxel.

- Error and cost function:

-

Assuming correct alignment, the transformed point should follow the distribution of the voxel:

\[e_i = Rp_t + t - \mu \\ \text{error}_i = e_i^T \Sigma^{-1} e_i\] - Here, $\Sigma$ is the covariance matrix of the voxel. $\Sigma^{-1}$ is the information matrix, and because we are getting its inverse, in practice, we want to add a small value to it $\Sigma + 10^{-3}I$

-

Jacobian update:

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} \frac{\partial e_i}{\partial R} = -Rp_t^\land \\ \frac{\partial e_i}{\partial t} = I \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]

-

- We also consider neighbor cells as well, because the point might actually belong to one of them. So we repeat step 3 for those voxels.

-

Maximum Likelihood Estimate (MLE):

\(\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & (R,t) = \text{argmin}_{R,t} [\sum e_i^t \Sigma^{-1} e_i] \\ & = \text{argmax}_{R,t} [\sum log(P(R q_i + t))] \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\)

- $H = \sum_i J_i^T info J_i$

- $b = -\sum_i J_i^T info e_i$

- $\Chi^2 = \sum_i e_i^T info e_i$

- $dx = H^{-1} b$

When the point cloud is sparse, we need to consider neighbor voxels. While it’s dense, 1 voxel is enough for matching.

Advantages and Weaknesses:

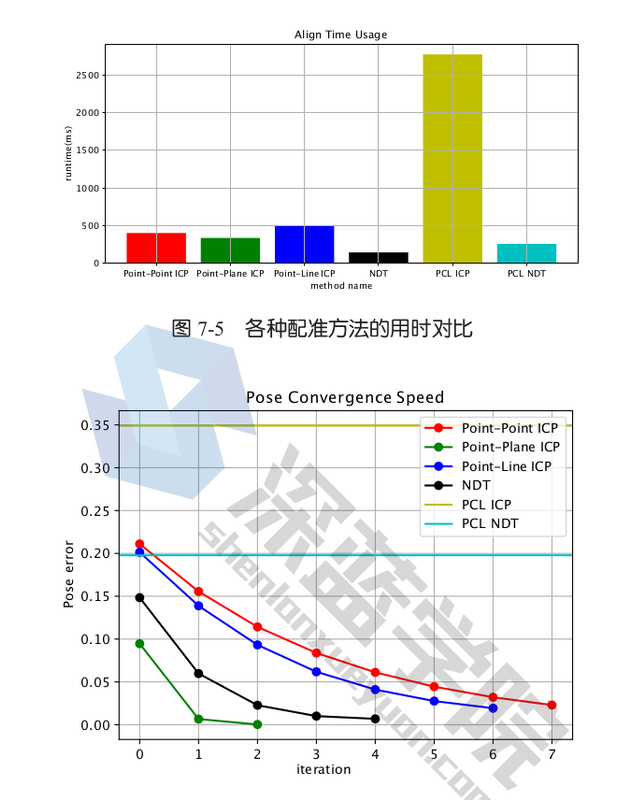

- NDT is very concise, and it does not need to consider plane, or line like ICP. It has become a widely-used baseline scan matching method.

- In general, it’s much faster than ICP methods, and its performance is a little worse than pt-plane ICP, but better than pt-pt ICP and is similar to pt-line ICP.

- However, like many other scan-matching method, NDT is prone to bad pose intialization. Also, voxel size could be a sensitive parameter.

This is more similar to the 2D version of NDT [2], and it different from the original paper [1]. But the underlying core is the same: in 2009, SE(3) manifold optimization was not popular, therefore the original paper used sin and cos to represent the derivative of the cost function. In reality, modifications / simplifications like this are common.

Another consideration is that we add a small positive value to the covariance matrix, because we need to get its inverse. When points happen to be on a line or a plane, elements on its least principal vectors will become zero.

Why NDT Works

We have points in the target cloud x1, x2...xi and source cloud x1', x2' ... xi'. The goal is to find the transform T such that $x1 \approx T x1’$ …

The mean and covarance matrix of the target cloud are $\mu_t$, $\Sigma_t$

The main idea of NDT is “if the true transform T* is found, the point distrbution of the source and the target clouds should match at each voxel.”

- We are actually turning the target cloud into a statistical field

- The main idea can also be phrased as “How probable is my source cloud if I move it by T?”

One necessary condition of the aforementioned optimization procedure to implement the main idea is:

“Probability Density Function value (PDF) of the source cloud w.r.t the target cloud is maximized when the ‘true transform’ T* is applied:”

Here is the proof:

- The product form above really is the joint PDF of all source cloud points w.r.t the target cloud. It’s equivalent to summing the log of it (a.k.a Mahalanobis Distance):

- Given a candidate pose T, the expected log-likelihood of all the source cloud points are

- $x_1’$, $x_2’$ are samples from the source cloud, and they are independent from each other. So they can be thought of as samples drawn from the source cloud distribution $X’$

- To calculate the expected log-likelihood, we have a refresher: the expectation of a function $g(X)$ is:

- So for a point in source cloud $X’$, we need to find the true corresponding pdf value of $ln(f(x_i’))$. Following the true transform, each point $x_i’$ is mapped to target point $x_{i} = (T^*)^{-1} x_{i}’$. But under the candidate pose T, they are mapoped to $x_{iT} = T^{-1} x_{i}’$. So the true corresponding pdf value of $ln(f(T^{-1}f(\mathbf{x}_i’)))$ should be:

- This form happens to be conveniently represented as

- And KL Divergence cannot be negative. See here for proof. So, now we have completed the proof

Then, the scan matching problem becomes finding the T such that the total Mahalanobis distance of source points w.r.t the target cloud is minimized.

Comparison

-

PCL is slower because we are using spatial hashing to find neighboring cells. PCL NDT uses a KD tree for that. A Kd-tree is built over the centroids of those cells

References

[1] M. Magnusson, The three-dimensional normal-distributions transform: an efficient representation for registra- tion, surface analysis, and loop detection. PhD thesis, Örebro universitet, 2009.

[2] P. Biber and W. Straßer, “The normal distributions transform: A new approach to laser scan matching,” in Proceedings 2003 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2003)(Cat. No. 03CH37453), vol. 3, pp. 2743–2748, IEEE, 2003.