Group Definition

Group (Group) is an algebraic structure consisting of a set and an operation. Denote the set as A, and the operation as ⋅. Then, the group can be written as G=(A,⋅).

- Closure (封闭性):

∀a1,a2∈A, a1⋅a2∈A. - Associativity (结合律):

∀a1,a2,a3∈A, (a1⋅a2)⋅a3=a1⋅(a2⋅a3) - Identity (幺元): There exists a0∈A such that

a⋅a0=a0⋅a=a - Inverse (逆):

∀a∈A,∃a_i∈A such that a⋅a_i=a_i⋅a=a0

If you speak mandarin, this rule is shortened to “封结幺逆”, which rhymes with “凤姐咬你” 💩

Some commonly seen groups include:

- The integers under addition (Z,+Z,+),

- Rational numbers under multiplication (excluding 0)

- General Linear Group

GL(n): The group ofn×ninvertible matrices under matrix multiplication. - Special Orthogonal Group

SO(n): The group of rotation matrices, whereSO(2)andSO(3)are the most common. - Special Euclidean Group

SE(n): The group of transformations in n-dimensional space, such asSE(2)andSE(3).

Abstract groups can be discrete (like integers) or continuous (like real numbers). SO(n) and SE(n) are continuous.

Lie Group, Lie Algebra and Manifold Definition

This is an intuitive introduction of Lie Group and Lie algebras, inspired by this post.

The Lie group is named after Sophus Lie. A group is a Lie group if it is a group, and is smooth (so integers are not a Lie group). Common Lie groups include:

SO(n),SE(n)GL(n)SU(n): Special unitary group of nxn complex matrices that preserve complex inner products.

Every Lie group has a Lie algebra. A Lie Algebra is a vector space that captures the infinitesimal structure of a Lie Group, e.g., the tangent space of the Lie Group. The general definition of Lie algebras is: a Lie algebra consists of a set V, a field F, and a binary operation ,. We also define [] as the Lie bracket:

- Closure:

∀X,Y∈V, [X,Y]∈V. - Bilinearity:

∀X,Y,Z∈V, ∀a,b∈F, $[aX+bY,Z]=a[X,Z]+b[Y,Z],[Z,aX+bY]=a[Z,X]+b[Z,Y].$ - Antisymmetry (or Skew-symmetry):

∀X∈V, [X,X]=0. - Jacobi Identity:

∀X,Y,Z∈V$[X,[Y,Z]]+[Y,[Z,X]]+[Z,[X,Y]]=0$

In the context of SO(3), the lie algebra so(3) describes the algebra of infinitesimal rotations. Specifically, it’s a skew matrix (see below), with Lie Bracket defined as $[X,Y]=XY−YX$

Manifold

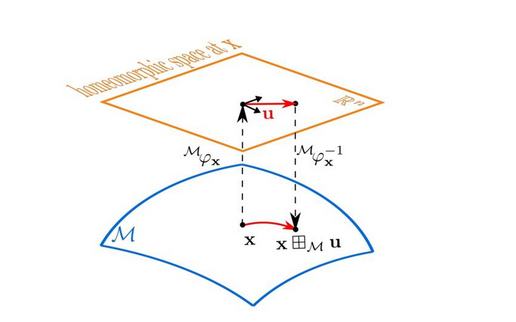

Manifold is a topological space which is locally Euclidean and globally connected.

- Topology means “a collection of open subsets”

- Each point on the manifold has a neighborhood that is homeomorphic (topologically equivalent) to an open subset of a Euclidean space $\mathbb{R}^n$.

Examples:

- Manifold embedded in $\mathbb{R}^n$ Example: if we want to find a manifold where all its points are on the 2D unit circle:

- (1,0) or (0,1) are on the manifold. But apparently not all points on the XY plane are on the circle.

- Polar cordinates $(r=1, \, \theta)$ describe the 1D manifold where all its points are continuous and generates the circle. The unit circle is said to be a “projection” of the 1D manifold onto the R2

- Following the same principle, a 3D sphere is a projection of the 2D manifold (theta, psi).

- Integers are not a Lie Group because they are discrete. But real numbers form a consecutive Lie Group.

- Elements in a Lie group can transition to each other through multiplication, inverse, and identity.

- All 3D rotation matrices form a group called “Special Orthogonal Group, SO(3)”, whose definition is $RR^T = I, det(R) = I$

- Their corresponding skew symmetric matrices are their Lie Algebra so(3). The exponential $exp(\phi^{\land}) = R$ is called “exponential mapping”

- A sphere is a manifold. Any two points on a sphere cannot produce another point on the sphere. However, at any point on the sphere, there’s a tangent plane where any two points there could add up to a point on the same plane (using the local coordinates there). Then, using some mapping, point addition result on the tangent plane can be projected onto the sphere. We describe that addition as:

- Where

x,yare points on the manifold, $\delta$ is a point on the tangent plane

Reference: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/545370811

SO(3)

SO(3) is the most common representation of rotation I’ve seen so far.

\[\begin{gather*} \exp(\hat{\omega}) = I + \frac{sin(\theta)}{\theta} \hat{\omega} + \frac{1 - cos(\theta)}{\theta} \hat{\omega}^2 \end{gather*}\]Common rotation matrices are:

\[\begin{gather*} R_x(\gamma) = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \cos \gamma & -\sin \gamma \\ 0 & \sin \gamma & \cos \gamma \end{bmatrix} R_y(\beta) = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \beta & 0 & \sin \beta \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ -\sin \beta & 0 & \cos \beta \end{bmatrix} R_z(\alpha) = \begin{bmatrix} \cos \alpha & -\sin \alpha & 0 \\ \sin \alpha & \cos \alpha & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{gather*}\]Skew Symmetric Matrices

Let $\phi \in R^3$ be a vector, and let $R \in SO(3)$ be a rotation matrix (i.e., $R^TR = I$ and $det(R)=1$). Define the “hat” (or wedge) operator $\phi^{\land}$ as the skew-symmetric matrix satisfying

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & \phi^{\land} x = \phi \times x \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]for any $x \in R^3$

From Skew Symmetric so(3) To SO(3)

We can see that R’R^T must be a skew matrix:

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & RR^T = I \\ & \Rightarrow (RR^T)' = R'R^T + RR'^T = 0 \\ & \Rightarrow R'R^T = -(RR'^T) = -(R'R^T)^T = \phi(t)^{\land} \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]Where $\phi(t)^{\land}$ the skew matrix of vector $\phi(t) = [\phi_1, \phi_2, \phi_1,]$

\[\begin{gather*} \phi(t)^{\land} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -\phi_3 & \phi_2 \\ \phi_3 & 0 & -\phi_1 \\ -\phi_2 & \phi_1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{gather*}\]Then, one can see that taking the direvative of R is equivalent to multiplying the skew matrix $\phi(t)^{\land}$ with it.

\(\begin{gather*}

R'R^TR = R' = \phi(t)^{\land} R

\end{gather*}\)

The above is also known as the Poisson Formula. If we define

\[\begin{gather*} w^{\land} = R^{T}R' \end{gather*}\]We have another form of the Poisson Formula:

\[\begin{gather*} R' = Rw^{\land} \end{gather*}\]Finally, do matrix exponential:

\[\begin{gather*} R(t) = exp(\phi(t)^{\land}) \end{gather*}\]Rodrigues Formula

Let’s represent the skew matrix as angle multiplied by a unit vector, $a^{\land}$

\[\begin{gather*} -\phi(t) = [\phi_1, \phi_2, \phi_3] = \phi a^{\land} \end{gather*}\]By writing out $a^{\land} a^{\land}$ “Unit” skew matrices have the below two properties:

\[\begin{gather*} a^{\land} a^{\land} = aa^T - I \\ a^{\land} a^{\land} a^{\land} = -a^{\land} \end{gather*}\]- One trick for the second formula is: $a^{\land} (a^{\land} a^{\land}) = a \times (aa^T - I) = -a^{\land}$

So, \(\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & exp(\phi^{\land}) = exp(\theta a^{\land}) = \frac{1}{n!}(\theta a^{\land})^n \\ & = I + \theta a^{\land} + \frac{1}{2!} \theta^2 a^{\land} a^{\land} + \frac{1}{3!} \theta^3 a^{\land} a^{\land} a^{\land} + ... \\ & = aa^T - a^{\land} a^{\land} + \theta a^{\land} + \frac{1}{2!} \theta^2 a^{\land} a^{\land} - \frac{1}{3!} \theta^3 a^{\land}... \\ & = aa^T + (\theta - \frac{1}{3!} \theta^3 + ...)a^{\land} - (1 - \frac{1}{2!} \theta^2 + ... )a^{\land} a^{\land} \\ & = aa^T + sin(\theta) a^{\land} -cos(\theta) a^{\land} a^{\land} \\ & = cos(\theta) + (I-cos(\theta)) aa^T + sin(\theta)a^{\land} \\ Or \\ & = I + (1-cos \theta) a^{\land} a^{\land} + sin \theta a^{\land} \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\)

Properties (伴随性质)

1. $ \phi^{\land} R = R (R^T \phi)^{\land}$

Proof:

First, we know from $ (a \times b) \cdot c = a \times (b \cdot c)$

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & (\phi^{\land} R)x = \phi^{\land}(Rx) \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]One key property about rotation is commutation: a rotated cross product is the same as the rotated vectors’ dot product.

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & R(a \times b) = (Ra) \times (Rb) \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]So on the right,

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & R (R^T \phi)^{\land} x= R((R^T \phi) \times x) \\ & = \phi \times (Rx) = (\phi^{\land} R)x \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]2. Conjugation: $\text{Exp} (P^{-1} A P)= P^{-1} \text{Exp} (A) P$

TODO?

3. $R^T \text{Exp}(\phi) R = \text{Exp}(R^T \phi)$

From 1, we know:

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & R^T \phi^{\land} R = (R^T \phi)^{\land} \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]Using 2, can derive:

\[\begin{gather*} \begin{aligned} & R^T \text{Exp}(\phi) R = \text{Exp}(R^T \phi) \end{aligned} \end{gather*}\]SO(3) Derivatives

- $\frac{\partial Ra}{\partial R} = -Ra^\land$, with $w$ being the underlying rotation vector